Pyramid Principle By Barbara Minto – Creating a convincing argument is hard work. Whether you want to present an idea through a thought leadership essay, a white paper, or even a simple memo, knowing where to start and what to say can be difficult. If this is a familiar problem, Barbara Minto’s classic book, The Pyramid Principle, may be right for you.

A collection of Minto’s 20 years of experience in corporate reporting and writing with McKinsey & Company. After leaving the company in 1973, he started his own consulting business. His goal was to teach business leaders how to write persuasively. A decade later, Minto incorporated these lessons

Pyramid Principle By Barbara Minto

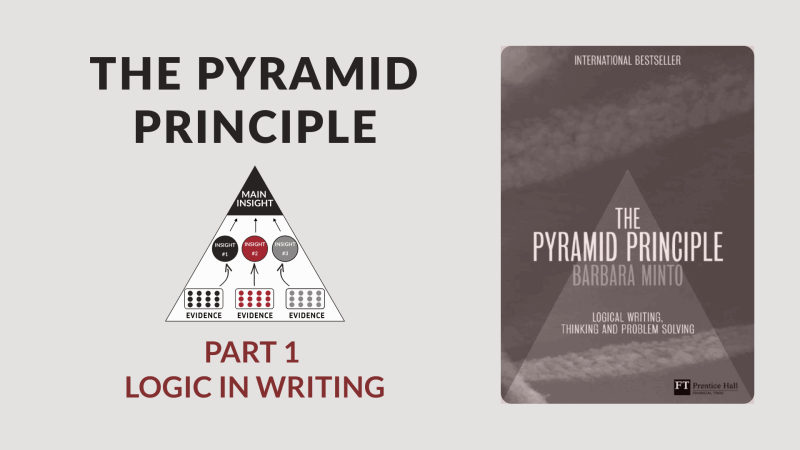

Minto’s thesis is that arguments are easier to understand—and more convincing—when arranged in a pyramidal hierarchy. This means organizing your argument in four layers: introduction, key statement, evidence, and conclusion. This arrangement not only makes it easier for the reader to understand your content, but also helps them move through the piece.

What Is The Minto Pyramid Principle? The Minto Pyramid Principle In A Nutshell

Although we recommend reading the entire book, we realize that not everyone has the time. Here are three main ideas from Minto that will help you make any argument strong and effective.

When proposing an idea, the temptation is to provide a narrative that explains how you arrived at the conclusion. However, Minto says it’s more persuasive to instead focus on a few key phrases about why the reader should take your advice and what actions they can take to do so. You can include your supporting evidence below the key points as a baseline for those who have time to read it but still accept your conclusion.

It’s just not the right time. Minto explains that “if you don’t tell [the reader] in advance what the relationship is, he will automatically look for similarities so he can group the dots.” By first presenting the idea and then explaining how the evidence relates to it, the reader will better understand the logic of your argument and likely find it more convincing.

For a good example of this idea in action, check out Siemens’ guide to harnessing technological innovation in industry, healthcare and infrastructure. The company’s key message is placed at the beginning of each section, helping the reader focus on the discussion while reading the details.

Argumentation Model For Planning A Research Article

A pyramid structure can also make your argument easier to remember. To illustrate, Minto gives an example of two shopping lists. In the first, the items are scattered without order, while the other is grouped into fruit, dairy and meat products. People are more likely to remember the items on the second list, even if they’re distracted, because the information is prepackaged for them, he says.

A current example here is HSBC’s white paper on the potentially inflated value of stocks, which does a fantastic job of structuring an argument into four simple, prepackaged ideas.

A statement to the reader that tells him something he does not know automatically raises a logical question in his mind. Writing to outline and then answer questions moves the reader through your argument as they seek answers to the questions you raise.

Minto says that the writer should continue this process until he “judges that the reader will no longer have reasonable questions.” The reader will be ready to see your documents.

The Pyramid Principle: Logic In Writing And Thinking (pre Owned Hardcover 9780273617105) By Barbara Minto

Minto suggests having at least two, but preferably three, supporting points for each argument. As he says these should be mutually exclusive and completely exhausting. This means that they should cover the entire debate and leave no room for doubt.

So, find the most compelling points or data that led you to your position, and then engage the reader with them. For example, the McKinsey Global Institute’s discussion paper on innovation in Europe shows how you can support complex ideas with easy numbers and strong deductive and deductive reasoning.

Begin this formula for each of your main ideas, with a new key phrase, explanation, and finally evidence, until your argument is complete. If your reader doesn’t agree with your conclusion by the end, at least they know how you got there. Minto believes that this creates a good basis for further discussions.

Once you have your structure in place, it’s time to write a compelling introduction. Minto suggests this formula for engaging the reader: situation, complication, question and answer. “You want to pique the reader’s interest by telling a story about that,” he says.

The Pyramid Principle: Logic In Writing And Thinking By Barbara Minto (hardcover, Revised Edition) For Sale Online

Start your report or other piece of writing with a statement that everyone agrees with or at least one is familiar with, and then complicate the situation. By telling readers that something isn’t as expected or has changed, Minto explains, they know what you’re saying is important. It also makes the reader ask “why?”, which needs to resolve the story. That should be your answer, Minto says.

Like a carrot on a stick, don’t leave your keynote until the very end, Minto cautions. A tactic like this is likely to reinforce rather than motivate. Instead, “put the reader in a position where he can decide whether he needs to continue or is willing to accept your results as they are.” If you’ve already written the body of your case, summarize the main points in one sentence and then add them to the introduction.

To see this in action, see Google’s white paper on security systems for cloud storage. In two lines, the reader knows exactly what the next 17 pages are about and worth reading. It is simple, concise and to the point and leads naturally into the body of the article.

Just as a pyramid helps the reader store information, headings help them guide the argument. If you’re a business writer creating a long-form article, this isn’t just a handy feature—it’s essential. Imagine the Cisco white paper on the competitive edge of networking without it. What could be an avalanche of text is instead an easy-to-follow, visually pleasing document that any reader can digest.

Pyramid Principles’ Applications

Minto lays out six rules for headlines that can be used to help your great business writing take the final step toward success.

With this in mind, even the longest report can be organized into bite-sized chunks that your readers can take in at a time.

Finally, once you’ve structured your argument, created a compelling introduction, and organized your document for easy navigation, you should edit your work and then edit it again.

If you can keep Minto’s constant recommendations as you write and edit, you’ll soon be producing reports, articles, emails, or other documents that can be persuasive on command. And if nothing else, I hope this summary has convinced you to find a copy of Minto’s excellent book.

The Minto Pyramid Principle: A Proven Framework For Crystal Clear Writing

Sam Henderson is an editor and proofreader with the Sydney-based Editorial Group. He now structures all of his arguments as a framework for structured thinking and communication. A method of ordering content for “everyday business documents” such as reports or presentations often used by consultants to present to clients.

At its heart is a simple idea that presentation logic should resemble a pyramid. The main recommendation is at the top of the page, which builds on the mid-level recommendations, each of which contains supporting tips.

Don’t jump to conclusions, but start by answering the customer’s question first and then list your supporting arguments. You create a pyramid of ideas held together by a single thought.

Each recommendation should have supporting points with relevant information (data, analysis, insights, metrics, conclusions, etc.) that follow a logical plan. For example below:

How To Boost Your Business Writing With Barbara Minto’s The Pyramid Principle

Minto documented this process in a 1987 book called The Pyramid Principle and later updated it in 2010 with Minto’s Pyramid Principle: Logic in Writing, Thinking, and Problem Solving.

As a consultant, the pyramid is mostly used by consultants. Minto’s writing on the pyramid is commonly required for new hires at large consulting firms and basically defines how most consultant presentations are structured.

This concept was developed by Barbara Minto, who was a McKinsey consultant in the 70s. Another reason for her importance is her contribution as a woman. She went to Harvard Business School without a bachelor’s degree and was the first female consultant at McKinsey & Company. Business engineering is the basic discipline that by. It combines different disciplines into one powerful subject so you can become a highly effective business person!

In 2011, I enrolled in the International MBA. Coming from a legal background, the MBA was a quick turnaround for me.

Powerful Communication With Mckinsey’s Pyramid Principle

I wanted to be in business (more like an entrepreneur than a manager). And I wanted to quickly find a career path to immigrate to the United States. it. (I am originally from Italy).

Fast forward to 2013, after completing my MBA, I managed to land a job as an analyst in California.

The pyramid principle barbara minto, the minto pyramid principle by barbara minto, minto pyramid principle summary, barbara minto pyramid principle, barbara minto pyramid principle book, barbara minto pyramid principle ppt, the pyramid principle by barbara minto pdf, the minto pyramid principle, barbara minto pyramid, barbara minto pyramid principle ebook, pyramid principle barbara minto pdf, pyramid principle minto pdf